In August 1914, the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary in a war against the Allied Powers of Great Britain, France and Russia.

Nine months later, its pasha leaders, Enver, Talaat and Djemal, fearing the revolt of Armenians under their jurisdiction, branded them as traitors and declared open season on murder.

The term Armenian genocide hadn’t yet been coined, but the news of what the Armenians began calling Medz Yeghern (Great Catastrophe) eventually reached the European capitals.

Djemal Pasha, fearing repercussions, came up with a secret plan to stop the genocide on a condition that the Allied Powers help him ditch his colleagues and enable him to become the sole ruler of Ottoman lands, circa 1916.

As a sweetening bonus, he promised the Russians the city of Constantinople and the Dardanelles.

Moscow expressed an interest in the plan, but not Paris or London. France wanted Cilicia and Greater Syria for itself. Great Britain’s imperial aims snubbed the desire of its people to end the suffering of Armenians.

So a defenseless population got slaughtered, inspiring Adolf Hitler to imagine the same end for the Jews.

In August 1992, Samantha Power—later to become President Obama’s ambassador to the United Nations—started her internship at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. A year before, Yugoslavia began to disintegrate along ethnic and sectarian lines.

This time the Bosnians faced the prospects of annihilation in the hands of Serbs. She joined her boss, Morton Abramowitz, the president of Washington think tank, to stop the slaughter of Bosnians.

Her internship ended a year later, but not the woes of Bosnians. She decided to visit their homeland and cover its tribulations as a war correspondent.

But the United Nations press office was in charge of the accreditation process and it required reporters to submit their bona fides.

Samantha Power had none, so she forged paperwork declaring herself a reporter of Foreign Policy magazine. It worked; she got the UN badge and went to Sarajevo to mingle with its beleaguered residents.

She became a stringer for several English publications.

Reflecting on her time in Bosnia she later noted: while Americans and Europeans were dithering, “Osama bin Laden set up training camps and radicalized secular Muslims who were tired of being killed for a religion they had never practiced.”

In fact, the architect of 9/11 would fly on a Bosnian passport for years undetected.

What was detected though was the palpable helplessness and hopelessness of Bosnians by Samantha Power.

Hoping for a better way to be of some help to them, she decided to attend Harvard Law School to become a prosecutor or judge in The Hague one day.

She was driving to Boston when she heard the news that America had entered the war to enforce peace on the warring sides. “I cried,” she confided to Senator Obama over a meal one evening.

In between, she wrote a book, A Problem From Hell, America and the Age of Genocide. It won her the Pulitzer Prize in 2003 for the best book in nonfiction.

Her chapter on the Kurdish genocide in Iraq is as vivid as it is damning to the American officials who staffed the American Embassy in Baghdad or the State Department in Washington, DC.

During the genocide, Americans looked the other way. After it, Iraq got rewarded for double credit (one billion dollars per year) to buy rice from Arkansas and wheat from Kansas, she writes.

Her chapter on the Armenian genocide has earned her the eternal enmity of Turkish diplomats in America who flock to her book readings and engage in denial debate, she says.

This “genocide chick,” as some came to call her, rose in the ranks of foreign policy establishment and became a staffer in Senator Obama’s office.

And when the junior senator from the state of Illinois decided to run for president of the United States, she signed up for his campaign to get him elected in 2008.

In a video posted on YouTube, she urged the Armenian-Americans to vote for him, because Barack Obama is a “true friend of Armenian people,” she asserts.

Unlike past presidents, he will call “the Armenian genocide a genocide,” she declares.

Senator Obama won the election and became the 44th president of the United States. Samantha Power followed him to the White House and became a member of his National Security Council.

Alas, Mr. Obama reneged on his promise to the Armenians and Samantha Power felt awful about her earlier plea to the Armenian Americans.

Undeterred, she encouraged President Obama to intervene on behalf of vulnerable populations, but doing so, for example in Libya, hasn’t exactly meant the restoration of law and order.

The president with a Nobel Peace Prize to his name and his UN ambassador with a Pulitzer Prize to her name—for raising the alarm bells on man’s inhumanity to man, threw in the towel when Syria came knocking on the door.

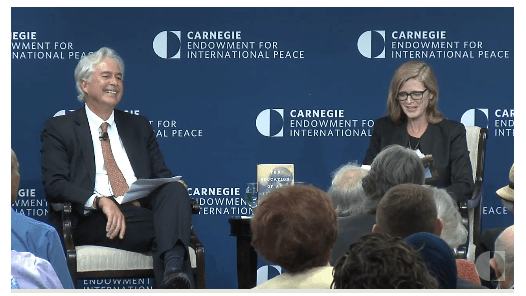

This month saw the publication of her latest book, The Education of an Idealist: A Memoir. I signed up for one of her book readings at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Her old boss Morton Abramowitz was there and was duly recognized. She reminisced about her time at the think tank and teased the new interns not to forge documents as she had done when she was green and in their shoes.

After reading a few passages from her book, she took questions. A dozen or so hands went up, including mine. But the question that landed like a bomb came from her old boss, Mr. Abramowitz.

He questioned the value and purpose of a think tank like Carnegie and said, “When I ran the endowment, we spent a huge amount of effort to promote war in the Balkans.

“[One day] Martti Ahtisaari, the president of Finland, came to me and said, Mr. President, you are not the head of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, you are the head of Carnegie Endowment for International War!

“Does a think tank have a serious mission other than analytical understanding? When does a think tank turn into an aggressive effort to change things?”

Samantha Power said, “I think Carnegie did more than what you are describing. Under your leadership, it pushed the Clinton Administration to go into Bosnia. The intervention did bring the conflict to an end.

“The peace, as you know, was ushered in about which the think tank had done far less thinking. What should a post-intervention Bosnia look like… That is a fair point. Not enough was done, but I don’t think you should take the responsibility for that…”

But what stuck with me was Mr. Abramowitz’s unanswered question about the Carnegie’s role in cultivating “analytical understanding.”

In May 1993, Mr. Abramowitz hosted Ahmet Turk and Leyla Zana, two Kurdish politicians, at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace for a breakfast meeting.

I happened to be their translator. The Kurdish politicians urged Mr. Abramowitz, who had worked in Turkey as America’s Ambassador for two years, to use his good offices for the cultivation of understanding (peace) between the Kurds and the Turks.

To my knowledge, Carnegie did nothing of the sort. In fact, the two Kurdish politicians never got invited back when Mr. Abramowitz was running the place.

The Kurdish Question remains unaddressed. Perhaps the present president of Carnegie, William J. Burns, will take up the challenge. If he does, I would strongly urge him to focus on the word “understanding.”

That is what is missing between the Kurds and their respective neighbors.

The Armenian genocide played a significant role in Adolf Hitler’s decision to commit the Jewish Holocaust. The Bosnian genocide may have had the same effect on Osama bin Laden’s decision to spark a war with the West.

Both could have been avoided had those who knew better, and had the power, paid attention to Edmund Burke’s observation:

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

I hope the Kurdish genocide will not generate its own monster one day down the road. But if it does, I pray the scholars of Carnegie and the diplomats of the State Department will draw the right lessons from it: indifference fuels and perpetuates genocide.

Kani Xulam @AKINinfo

This op-ed first appeared on the website of Counterpunch.

0 Comments