Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837) didn’t live long enough to see a free Italy, but wrote some of the most moving verses to lament his homeland’s subjugation by France under Napoleon Bonaparte.

In a poem titled, To Italy, he mourns the loss of Italian soldiers in Bonaparte’s ill-fated Russian campaign with these haunting words that can easily pass for Kurdish fighters who died in Korea for Turkish Adnan Menderes or Kuwait for Arab Saddam Hussein.

Oh miserable is he—who dies in battle,

not for his country’s soil, his faithful wife

and precious children,

but he dies serving someone else,

dies at the hand’s of that man’s enemies,

and can’t say at the end: Beloved native land,

the life you gave me I give back to you.

Italians devoured his poems like hungry wolves and set out to liberate Italy from the yoke of France and Austria.

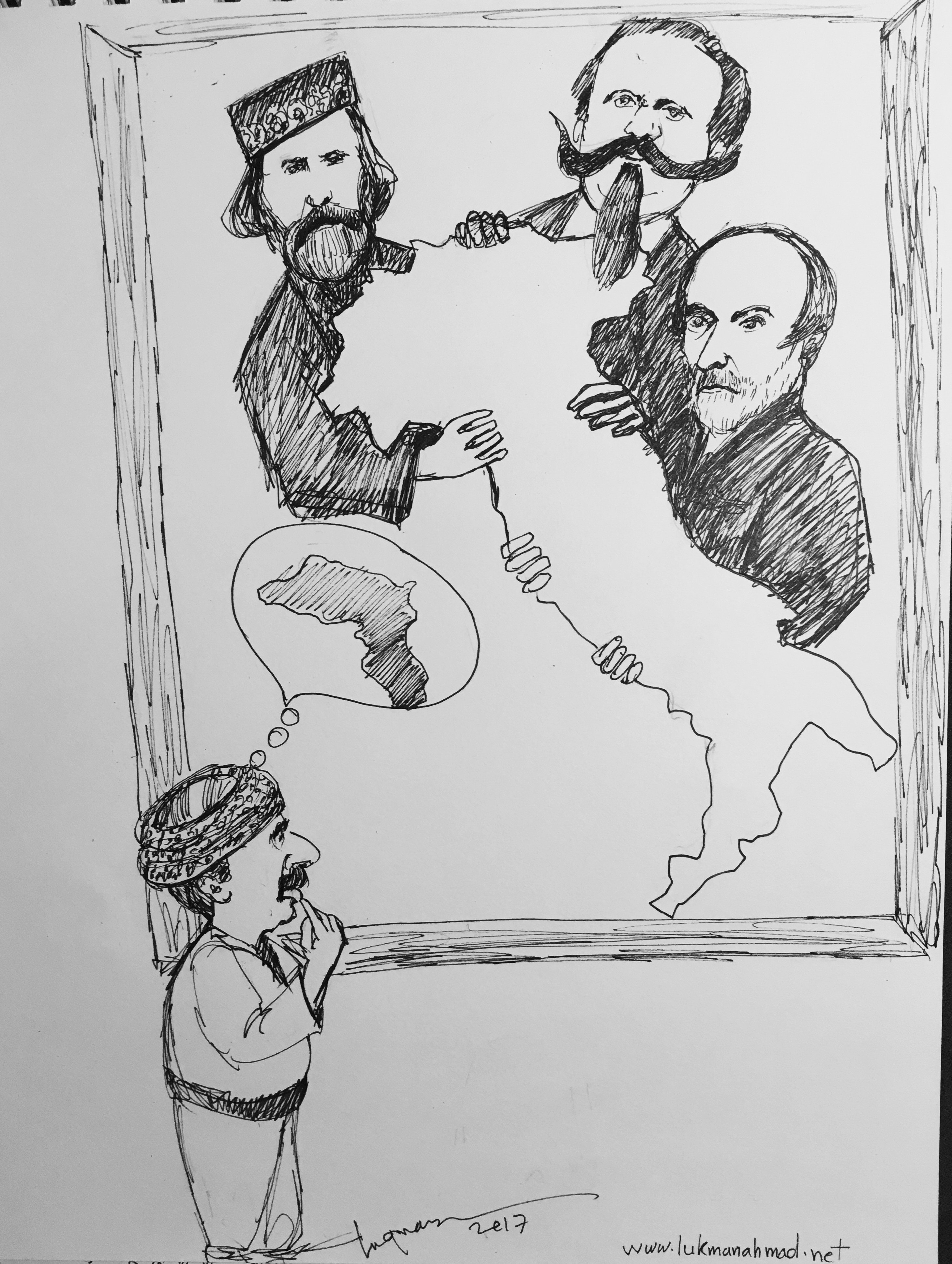

Three of them deserve special Kurdish notice—for what may be called the soul, brain and sword of Italian freedom.

Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872) spoke to the soul of Italians with his passion for liberty. As if addressing the stateless peoples all over the world, he said:

“Do not beguile yourselves with the hope of emancipation from unjust social conditions if you do not first conquer a country for yourselves.”

“Without country,” he harangued his fellow Italians: “you are the bastards of humanity.”

Truer words have never been uttered so succinctly on behalf of freedom anywhere in the world.

Mazzini may have voiced the deepest yearnings of Italian patriots, but the brain behind unification was Count Cavour (1810-1861), the prime minister of King Victor Emmanuel in the Kingdom of Piedmont, a small Italian state bordering France.

Unlike Mazzini, who advocated mingling blood and iron for liberation, Cavour opted for diplomacy, especially with Great Britain, the superpower of 19th century, to achieve the same goal.

So when Great Britain, together with France and Ottoman Empire, declared war on Russia to preserve the territorial integrity of the crumbling Turkish state for geopolitical reasons, Count Cavour rushed in 15,000 Italian soldiers to Crimea to help Great Britain win the war in 1853.

Four years later, the same Cavour allowed Russia to establish a naval base in Piedmont.

He also convinced his king to exchange the province of Savoy and the city of Nice, the birthplace of Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi, for the strategic friendship of France against Austria.

He might be called “a man for all seasons” and we Kurds might see some of our own leaders in him. But this indefatigable Kissinger of Italy also earned the well-deserved title of liar for all times.

The man who actually freed Italy and captured the imagination of Italians and Europeans alike was the native of Nice, Guiseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882). His contemporaries likened him to Spartan Leonidas, Roman Cincinnatus and American George Washington.

Britain’s poet laureate Lord Tennyson, after planting a tree in his honor, movingly wrote:

Or watch the waving pine which here

The warrior of Caprera set,

A name that earth will not forget

Till earth has roll’d her latest year—.

Liberation movements used to command the attention of 19th century poets. At the dawn of 21st century, the bards have gone quiet, but the prose writers are busy conflating our desire to be free, alas, with selfishness.

In Italy, the decisive countdown for liberation started on May 5, 1860. With the help of Cavour, Garibaldi and his Mille (thousand) Redshirts sailed to Marsala in western Sicily with a hoodwinking from Great Britain.

Four months later, all of Sicily and southern Italy were in the hands of 21 thousand Redshirts and Garibaldi. Italians were winning and those dying could finally say, as Leopardi wanted them to:

“Beloved native land,

the life you gave me I give back to you.”

Ten years later—with a little bit of help from Germany, modern Italy was born.

But instead of focusing its energies on making Italians better patriots, it foolishly aspired to become an imperial power with fleeting forays into Eritrea, Somalia, Libya, Dodecanese Islands, and Ethiopia.

Unheeded observation of Chancellor Bismarck was spot-on: “Italy has a large appetite but false teeth.”

Leopardi, the Italian poet, can finally rest in peace. These days, Italians are not dying at the outskirts of Moscow from cold. They are busy selling Russians designer clothes and luxury cars to make up for Lenin’s forced, but failed experiment in equality.

Kani Xulam on Twitter: @AKINinfo

A slightly edited version of this op-ed originally appeared in Kurdistan24.net

0 Comments