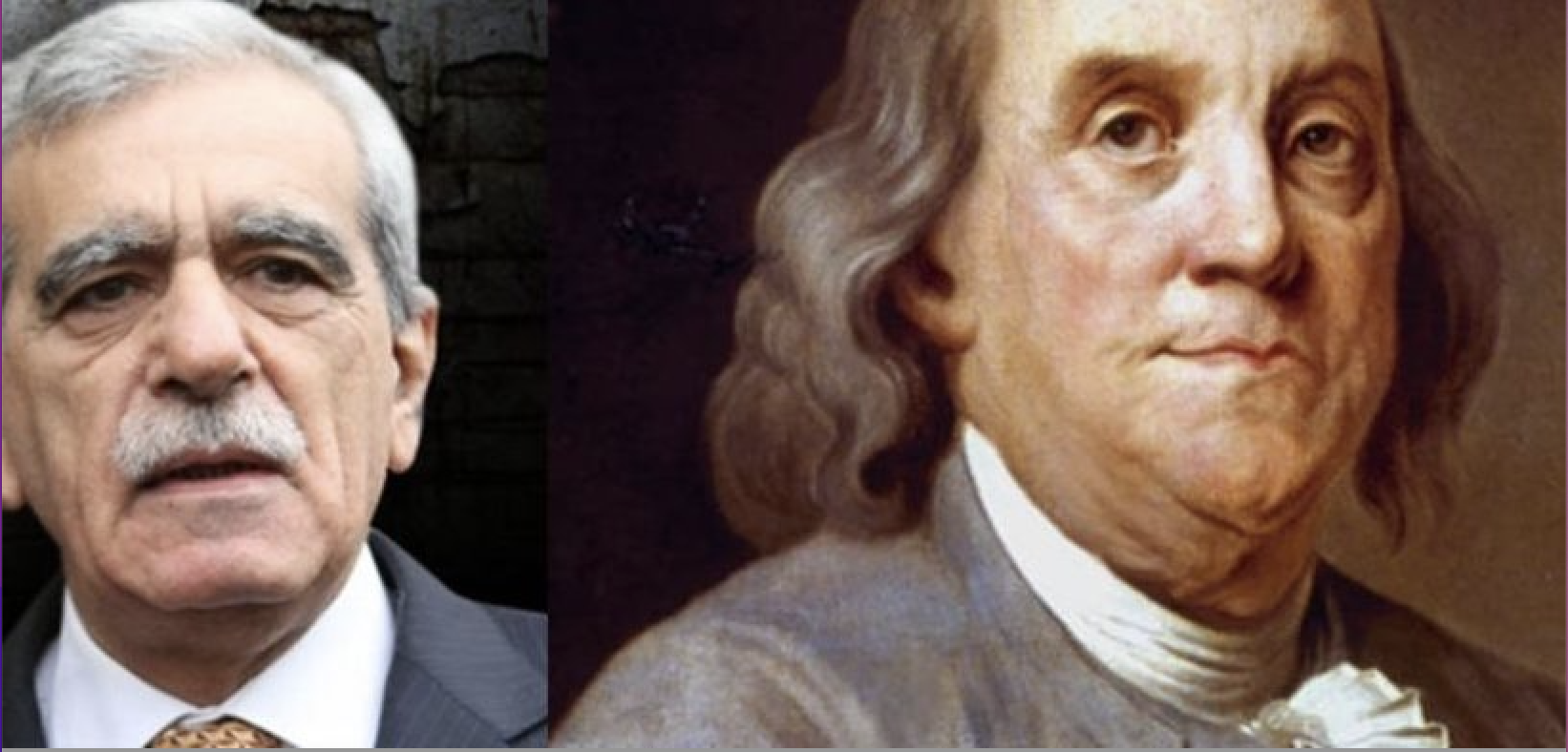

Journalists often equate Erdogan with Putin, Clinton with Blair, Reagan with Thatcher. I’d like to make another comparison: Turk and Franklin! If your hand went to your head involuntarily, bear with me, this duo leaves Erdogan and Putin comparison in the shade!

This essay is about Benjamin Franklin—highlighting his exploits that may shed some light on the Kurdish struggle for freedom. Another one about Ahmet Turk is in order—hopefully, someone with access to him or his files will write it. Franklin gamed the English to free the Americans. Turk may yet guide the Kurds to politically distance them from the Turks—for the good of both peoples.

Besides, just as comparing doctors is good for consumers, comparing political leaders is good for citizens. Choice is the essence of democracy. By comparing and choosing, I am doing my bit for democracy. If it helps you make an informed decision—we are making progress in the Middle East.

Benjamin Franklin is an American icon. He was born in 1706 and died in 1790. His 84 years in our world are often divided into two halves. In the first half, he declared his own independence. In the second, he worked for the independence of the United States.

Most Kurds who are politically aware and socially conscious would probably be curious about the second half of Franklin’s life. But Shakespeare cautions us to take the broader view. In his words, “What’s past is prologue.”

That means we must know the first half of Franklin’s life to really make sense of the second half. I will take on his whole life to look for similarities and differences too between the aging man of the Kurdish struggle and the old man of the American Republic. I venture to guess if you could bring them together, they would part friends after an hour’s conversation.

Benjamin Franklin came of age in Boston. In Philadelphia, where he moved as a teenager, he bloomed and blossomed. Both cities claim him as a native son. America honors him as a Founding Father. His image graces the 100-dollar bill.

When Benjamin Franklin was born, Boston had a population of 7,000. A thousand homes dotted its cityscape. A thousand ships anchored at its harbor.

Puritans dominated its politics. Piety was enforced. Sinners were penalized—in public. It was a Christian theocracy from head to toe. See The Scarlet Letter of Nathaniel Hawthorne. See The Crucible of Arthur Miller.

Benjamin Franklin grew up in this deeply religious environment. He learned how to read and write at an early age. He was the tenth child of a second marriage and was offered to God as a tithe—to become a minister in New England.

But as the Yiddish saying goes, “Man makes plans, God laughs!”

Those who wanted to be ministers often started at Boston Latin School. Franklin too was registered there. He excelled in his studies, but not his piety. For example, he thought his father’s prayers (before meals) were too long and tedious and suggested an alternative: just one prayer for an entire winter—to save time!

His father was not amused.

He rejected young Franklin’s suggestion. He also changed his mind about dedicating his son to God. Benjamin Franklin the student became Benjamin Franklin the apprentice at his brother’s printing shop.

At Boston Latin School, he had loved reading books. At the printing shop, he was tasked with making them. But he never lost his interest in books and used all his savings to collect a library of his own—accumulating as many as 3,747 volumes when he closed his eyes to the world.

But when his father’s books, plus the ones that he purchased through his savings, didn’t satisfy his thirst for learning, he obliged his friends, especially those working at bookstores, to lend him books for the night when the shops were closed.

At the Franklins, when a book was borrowed, he was the last to sleep and the first to wake up, so that he could squeeze in as much reading as he could and return the book to its rightful owner before the shops opened.

These borrowed books included the works of Plato, Plutarch, and Tacitus. He also learned about vegetarians and became one. But he modified vegetarianism by saying it was all right to eat fish, because the fish were eating other fish!

A good reader can become a good writer. Benjamin Franklin was an ardent reader and an aspiring writer. He wrote essays after work and submitted them to his brother’s newspaper, the New-England Courant. Alas, they were rejected.

Franklin really wanted to see his name in print and decided to submit newer pieces under the assumed name of “Silence Dogood.” They were accepted. But when he revealed his identity, his work was once again thrown into the trash can.

As an indentured worker, Benjamin Franklin was at the mercy of his boss. His brother would sometimes beat him—and Franklin could not do anything about it. America, he knew, had other cities. He began to look beyond its small hills.

At seventeen, he left Boston and became a runaway fugitive. New York offered him a refuge, but not a job. Philadelphia gave him both. He became a Philadelphian for the rest of his life.

Franklin took to the City of Brotherly Love the way a duck takes to water. Four years later, he owned his own printing shop. Nine years after that, he entered into a common law partnership with Deborah Read and started his own family.

In the 18th century, America doubled its population every twenty years. The more people there were, the more business there was for Benjamin Franklin’s printing shop. 25 years later, he retired from his work and without knowing it stumbled into another one: that of freeing and building the United States.

In 1757, the Pennsylvania Assembly sent him to London as its representative. On the way to Britain, near the Scilly Isles, his ship was attacked by the pirates and hit rocks in the fog. He survived to tell his tale and it is a very revealing one!

In a letter to his wife, he wrote, “were I a Roman Catholic, perhaps I should on this occasion vow to build a chapel to some saint; But as I am not, if I were to vow at all, it should be to build a lighthouse.”

A question for the reader of this essay who may be from the Middle East as I am:

Now that we have had our own brush with Islamic theocracy, is it possible that we too will soon graduate from the age of faith to that of reason as Benjamin Franklin and his contemporaries did in the United States?

In London, Franklin wasn’t just a representative of Pennsylvania, but also a well-known scientist. His discovery that lightning was electricity had turned him into a household name in Europe.

The Royal Society in Britain inducted him as a member. The French Academy followed suit.

Franklin ended up spending close to 13 years in Britain and Europe. He rejected the notion that the British Parliament had the right to impose taxes in the colonies. Representation came before taxation, he argued. His arguments, alas, were dismissed.

As the 1770s approached, the relations between Britain and its colonies worsened. London imposed taxes on tea in the colonies. Americans liked their tea, but not its taxes, and in Boston, dumped it into the harbor.

London, as can be expected, was furious. Benjamin Franklin, the highest ranking American official in the British capital, was ordered to appear before the Privy Council for the wayward behavior of his fellow colonists.

The hearing was held in a room called the “cockpit.” In that chamber, Henry VIII had watched fighting cocks during his reign. In that hall, Solicitor General Alexander Wedderburn was now going to teach Franklin a lesson that, he hoped, would turn Franklin into a puppy and Americans into a flock of sheep.

He was disappointed.

Benjamin Franklin ignored him—gave him a silent treatment. It was a form of nonviolent resistance.

Gandhi, following the same tactic, with the help of millions on his side, did the same and more—stopped cooperating with the unjust laws of Britain in India, and freed the subcontinent. Dr. King, cooperating with white activists such as Stanley Levison, emulated the Indian in America and sent the Jim Crow laws to the museums.

Very few Kurds have looked into this type of nonviolent resistance to oppression across the Middle East. Perhaps Ahmet Turk and his friends will do so in the remaining years of their lives—freeing Turks, Arabs and Persians from their predatory racism and Kurds their withering bondage.

After the dressing down in the “Cockpit,” Franklin knew it was time to return home. On the ship to Philadelphia, he confided to his grandson that America’s better days still lay ahead. His new freedom plan included three imperatives:

“Make money, be economical, and have children.”

Money opened doors. Frugality enabled one’s savings to become a powerful tool. American born children, given America’s birth rate, would enable America to catch up with Britain’s population in fifty years.

With peaceful evolution, not bloody revolution, Franklin was going to bring the British Empire to its senses.

But when he landed in Philadelphia, America was in full revolt. A day later, he was elected a representative of Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress. In the initial deliberations, he remained a dove: he didn’t want to submit to Britain; he also didn’t want to attack it.

But the presence of thousands of domineering British soldiers in the colonies made his agenda impossible.

Benjamin Franklin felt America’s hand had been forced. He was now a rebel patriot like any other. He urged his son, the governor of New Jersey, to do the same. Alas, he remained loyal to Britain.

When Congress appointed Franklin as its representative in Paris, he was game. Britain had defeated France in the Seven Years War. Now, it was Franklin’s plan, and prayer too, to get France on the side of the colonies to even the score.

Would Paris go for it?

The old man’s charm was contagious. He counted the likes of Voltaire, Brillon, and Helvetius among his friends. Marquis de Lafayette, Baron von Steuben, and Casimir Pulaski reported to him for help. He put them on the first ship to the colonies.

The American victory in Saratoga in 1777 sealed Britain’s fate. That is when France sided with America financially, militarily and diplomatically. The battle of Yorktown acted as coup de grâce.

By the end of the war, France had loaned the colonies 25 million livres and spent over a billion of its own.

Reflecting on the expenditures of the American Revolution, Franklin would note:

“If they [the Americans] had given me a fourth of the money they have spent on the war, we should have had our independence without spending a drop of blood. I would have bought all the Parliament, the whole government of Britain.”

Franklin’s comment recalls King Philip II of Macedon’s observation, “A mule laden with gold can enter any town!”

Kurds would do well to reflect on Franklin as well as King Philip II. Blood is not the only currency of freedom. Liberty has other tools in its arsenal.

While these sums were spent and America’s independence seemed guaranteed, the French were acclaimed across the United States as well as Benjamin Franklin. A new town in Massachusetts decided to change its name from Exeter to Franklin.

A few years later, one of its residents wrote to Franklin and requested that he purchase a bell for their church. Mr. Franklin, a deliberative man, decided to consult his sister, a resident of Boston, for some feedback.

She was against it. She wrote, “They need a bell as much as a toad needs a tail.”

He agreed with her. He sent the church a trunk with 116 books on science and the art of government. Ninety-two of these books still exist and are on display at Franklin Public Library, in Franklin, Massachusetts.

If you are a book lover—and you must be if you have made it this far—you should consider visiting this collection in the United States. You would be honoring not just the old man, but also his fervent belief that the change that matters the most takes place within, and books are the essential ingredients of this salutary change.

Writing to a friend in London, Franklin got into his reasons for why he had sent them books instead of a bell. In his words, “Sense being preferable to sound.” In a way, he was revisiting his old letter to his wife, in which, he had expressed his preference for utility as a condition for his gifts.

This particular gift, although modest by today’s standards, inspired Andrew Carnegie to build, from his own funds, 1,689 public libraries across the United States.

Was Benjamin Franklin perfect? No, he wasn’t. He owned two slaves. One ran away and became free in England. The fate of the other is not known.

After America’s independence, Franklin became an abolitionist and was elected president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery.

In a petition to the first Congress of the United States, he urged not only for the abolition of slavery, but also financial aid “to the distressed race.”

The Congress chose to disregard his petition.

Franklin had other means at his disposal. For example, he penned an essay—distributing it through his newspaper—a hilarious parody, as “Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim,” addressed it to the Divan of Algiers, on the self-evident need—blessed by the holy book, the Qur’an—to preserve and perpetuate White slavery in north Africa.

Mr. Ibrahim argued that Whites made excellent slaves—worked harder than Blacks in the fields and could stand the blazing sun much better than the Africans!

Franklin also left a portion of his estate to his daughter, Sally and her husband, Richard, as long as the slave they had was freed.

They freed him.

The French statesman Turgot wrote of Benjamin Franklin after his death, “He seized the lightning from Heaven and the scepter from the Tyrants.” Franklin did both and increased the amount of happiness in the world.

The “distressed” Kurds would do well to follow his example.

Ps I: If Ahmet Turk does in his life what Benjamin Franklin did in his, I would be willing to urge my town elders in Kurdistan to change its name to Turk. Like Franklin, it might inspire reflections, such as this one, 300 years from now.

PS II: Kurds can one day forgive Turks. Turks will not forgive themselves. They are living with their crimes. It is a heavy burden to bear.

Kani Xulam (@AKINinfo).

This essay originally appeared at News About Turkey.

0 Comments