One English transplant to America, the late Christopher Hitchens, very much hoped he would. And he didn’t just engage in wishful thinking, he also wrote a book, Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, and dedicated it to President Jalal Talabani, the first ever duly elected head of state in the history of Mesopotamia.

That fact in itself doesn’t say if Mr. Talabani emulated Mr. Washington. What it signifies is that Mr. Hitchens wrote a book about Thomas Paine and Mr. Paine, if you have read his book, Rights of Man, had dedicated it to President George Washington, the first duly elected head of state in America since antiquity.

Two intellectuals placed their hopes on two presidents. Did the American and Kurdish politicians fulfill those expectations? The record is not good. What follows is an analysis of the authors’ high aims and dashed longings in America and Europe of 1770s and 1810s and in Kurdistan and Iraq of 1970s and 2010s.

Thomas Paine is best known as a founding father of America. Alas, he hasn’t enjoyed the limelight like Adams, Jefferson, Hamilton or Madison. Some have compared him to Che Guevara. Others to Marquis de Lafayette. The abolitionist John Brown was fond of his anti-slavery stand. Lincoln modelled some of his writing after him.

Before adding American to his English name, like English American, Mr. Paine was a civil servant in England who had tried to make a living in Lewes. His colleagues were impressed by his amiability and diction and thought he should represent them, as a lobbyist, for higher pay in London.

He tried and was summarily fired. As luck would have it, he crossed paths with Benjamin Franklin. The American nudged him to seek his fortune in the New World and handed him a letter of recommendation too.

In the fall of 1774, he undertook the trans-Atlantic journey. That fateful crossing maybe compared to that of Christopher Columbus. The Italian had bumped into a continent instead of India. The Englishman bumped into a revolution instead of an ordinary job in a new land.

As to Mr. Franklin, without knowing it, he had sent his homeland one of its greatest revolutionaries of all time.

But Mr. Paine almost failed to complete his voyage. A typhoid breakout on his ship just about sent him to the bottom of Atlantic Ocean as shark food. He was barely conscious when the ship carrying his prone body docked at the Philadelphia Harbor. The chance discovery of Mr. Franklin’s letter in his pocket saved his life.

As the year 1775 dawned, he was himself again and became a regular at a downtown bookstore. Its owner, Robert Aitken, offered him a job as an editor of Pennsylvania Magazine. He wrote feverishly under various assumed names and more than doubled its popularity in a matter of months.

Four months later, in April, the British soldiers shed American blood in Lexington and Concord. Mr. Paine’s magazine adopted the revolutionary cause as its own.

The fighting may have started near Boston, but it was in Philadelphia that the Second Continental Congress met a month later. For Paine, that was as good as “the mountain coming to Mohammad.” He hobnobbed with its delegates. He impressed them with his thrilling diction and nimble pen.

A prominent Philadelphian, Benjamin Rush, urged him to wield his pen in defense of the revolution.

That was like asking a lion to roar!

He called his first draft Plain Truth, but Mr. Rush prevailed on him to change its title to Common Sense, and urged him to go easy on the words, independence and republicanism. But Mr. Paine found other ways to say the same things.

Here is what a discarded sentence—on the urgings of Benjamin Franklin, looked like:

“A greater absurdity cannot be conceived of, than three million people running to their seacoast every time a ship arrives from London, to know what portions of liberty they should enjoy.”

Now imagine the same Mr. Paine wielding his pen for the cause of Kurds and Kurdistan today:

“40 million Kurds can’t wait forever for Ankara, Tehran, Baghdad and Damascus to tell them how long or short is their leash in a foreign language that degrades them from cradle to grave!”

The final draft of Common Sense that saw the light of day still retains its powerful cutting-edge tone after 244 years:

“Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia, and Africa, have long expelled her. Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart.”

America was its last refuge, he said, and its inhabitants were tasked with a struggle in millennial terms. Again, in Mr. Paine’s words:

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand …”

For that birthday’s sake, he even donned his musket, but was ordered to compose prose to boost the morale of the troops. This passage may remind some of the Kurdish readers the hearty poetry of our own Cegerxwin:

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. …”

Americans were moved by his words and bought his works by the thousands. Common Sense became the best seller and its profits were dedicated to the coffers of the Continental Army.

“Without the pen of Paine,” wrote John Adams, the second American president, “the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain.”

This was perhaps a bit overstating the fact, but just a bit. America’s good cause had an equally powerful patron, France. The happy union of the doggedness of Americans coupled with the strategic support of the French king tipped the scale in favor of the rebel Americans for good.

Hello, State Department, Americans were once rebels too!

Thirteen years later, France followed suit.

Unlike the American Revolution, the French Revolution took a turn for the worse. Edmund Burke, a member of House of Commons, decried its excesses with a tract of his own, Reflections on the Revolution in France, and predicted, uncannily one might add, its usurpation by a dictator.

Napoleon, eventually, became that absolute ruler. But in between, Mr. Lafayette handed the key of Bastille prison to Mr. Paine to deliver it to President George Washington as a gift. To this day, it hangs on the wall of Mr. Washington’s home in Mount Vernon.

In the meantime, Mr. Paine sat down to write his own defense of French Revolution by way of a response to Mr. Burke. He called it, Rights of Man, and dedicated it, as noted earlier, to the hero of his adopted land, his old friend, President George Washington.

It became the second best-selling book after the Bible in Europe. Four cities in France offered Mr. Paine honorary citizenship. One, Calais, sent him to Paris as its representative. The kings and nobility hated the new book; the ordinary people cherished it.

The late Christopher Hitchens, like Thomas Paine, was a transplanted Englishman to America. Like him, he led a storied life and qualified for that rare distinction, a public intellectual.

Like his idol Socrates, he defended truth as he saw it with every fiber of his being.

Like him also, he was not afraid of controversial topics. He called Henry Kissinger a war criminal to the delight of Chileans, Cypriots and Kurds and it stuck. Even Mother Teresa, now a canonized saint in the Catholic Church, was not impervious to his withering volleys.

But Kurds should pay heed to his criticism of Edward Said. He reminded the author of Orientalism that he had gone easy on the pernicious influence of Turkish imperialism in Eastern Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East.

Mr. Hitchens was a frequent visitor to the Middle East and knew of our people and its various leaders. A former Trotskyite, he was well equipped. Mr. Talabani was a reformed kindred spirit. Mr. Barham Salih was, well smooth—he could sell vodka to Russians and sand to Saudis without skipping a beat.

Mr. Abdullah Ocalan stood in a class of his own. He disliked him as much as Trotsky disliked Stalin. He viewed Mr. Ocalan as a liability and probably thanked Americans, Israelis, and Turks for conspiring to distance him from the Kurds and their rightful aspirations.

If this leaves you with the impression that he was indifferent to the plight of Kurds in Turkey, it shouldn’t. No one has stated the overall Kurdish Question in the English language as succinctly as he has:

“The future of civilized discourse in Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria is inextricably bound up with [the fate of Kurds.]”

So, we are in possession of the key to the Middle Eastern “heaven” on earth after all! Alas, those who speak for our neighbors would rather spend the rest of their lives in hell, with us, than see us, all of us, enjoy the blessings of a free Middle East in our respective homelands!

Speaking of the Kurdish desire for freedom, referring to the status quo huggers, Mr. Hitchens said:

“I am sorry for those who have never had the experience seeing the victory of a national liberation movement, and I feel cold contempt for those who jeer at it.”

Mr. Paine and Mr. Hitchens were enablers, gifted with that rare quality to see behind the mountains. Both were sworn enemies of theocracy and hereditary power. For Paine, the ultimate truth was reason; for Hitchens, the unvarnished facts.

Did Mr. Washington and Mr. Talabani embody these tendencies? Mr. Paine wished for the New World to regenerate the Old World and urged Mr. Washington to do his part in the emancipation of Europe.

It didn’t happen on his watch. Europe’s journey towards freedom has been bumpy but steady. The rest of the Old World, with a few exceptions, still reels from the abuses of despots who cling to power till death—sometimes, alas, with the help of Uncle Sam.

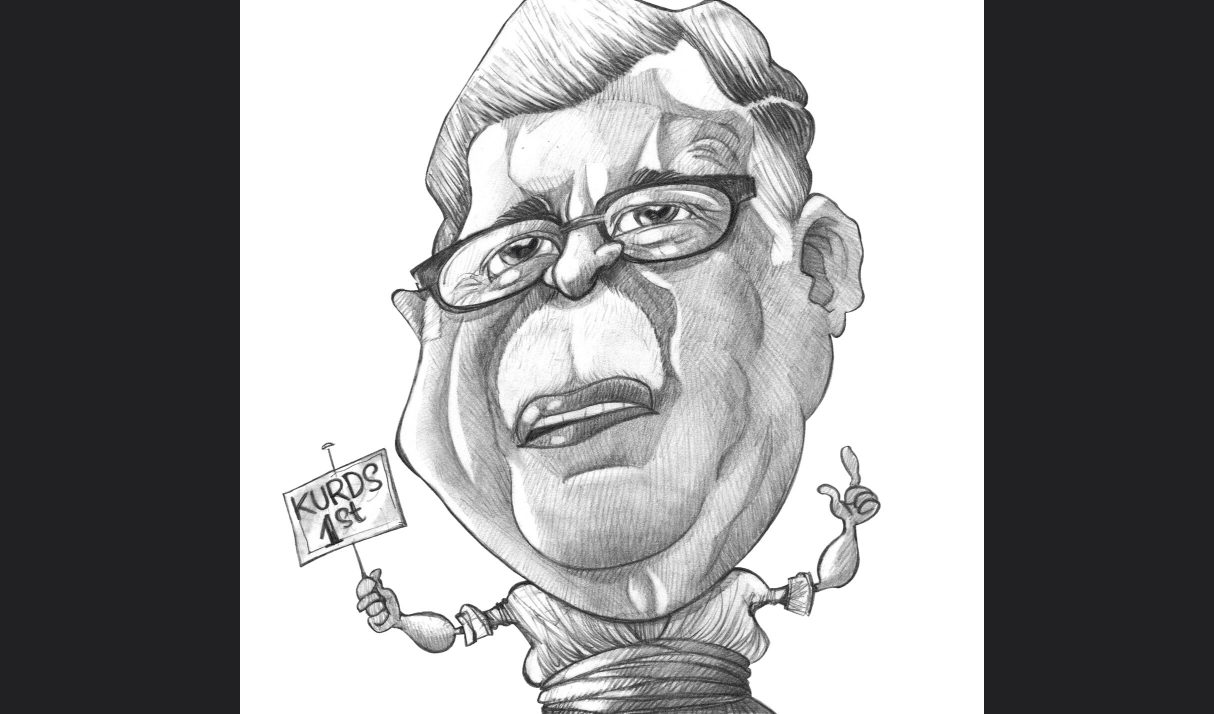

When Mr. Hitchens dedicated his book to President Talabani, he too expressed high hopes for its recipient. He described Mr. Talabani as a “sworn foe of fascism and theocracy” and honored his political and military leadership in the national liberation struggle of Kurds.

The clincher: “In the hope that his long struggle will be successful and will inspire emulation.”

Has it?

A few questions are in order: Did Mr. Washington read Mr. Paine’s book? Did he agree with its expressed ideals? How about Mr. Talabani? Their libraries contain both books. Americans and Kurds would do well to visit their dusty jackets.

Alas, neither president took the messages of the books that were dedicated to them to heart. Their good fortunes did not translate to a noticeable increase in their goodwill or judgements.

Mr. Paine was freedom’s trumpet and wanted its blessings for everyone. In his first year in Philadelphia, he penned an essay, African Slavery in America, for Pennsylvania Journal, which led to the establishment of the first American anti-slavery of society. He became one of its founders.

When Mr. Washington was on his death bed, he had 123 slaves to his name. He struggled over their emancipation. He left a will to his wife declaring them free upon her death. If it were up to Mr. Paine, Mr. Washington would have never owned them in the first place and heeded Euripides instead:

“Sufficiency is enough for men of sense.”

When Mr. Talabani became the president of Iraq, he went on an official visit to Iran. Native and foreign reporters accompanied him in the presidential plane. When his plane was still in the air, an aide of the Kurdish president handed out thick envelopes to all the passengers.

One of them was a reporter from The New Yorker, Jon Lee Anderson. When he opened his envelope, twenty crisp Benjamin Franklins stared at him in the face. When he asked what the money was for, he was told, it is “a gift” from President Talabani!

Mr. Anderson returned the money intact. No one else apparently did.

We don’t know what the late Christopher Hitchens thought of this clumsy effort at bribery. We do know that the “president” whom the Kurdish president replaced, Saddam Hussein, used to gift brand new Mercedes Benz sedans to reporters for sympathetic coverage when he was calling the shots.

There is a big difference, of course, between $2,000 and $200,000! Did President Talabani finally direct the Middle East in the right direction?

The new president of Iraq, Barham Salih, is also an old friend of Mr. Hitchens. Let’s hope President Salih will take Mr. Hitchens’ fondest hope for a clean government, in the heart of the Middle East, to heart!

May the rest of the Middle East then sit up, take notice, and emulate it too for the sake of our children!

Rest in peace President George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799), Thomas Paine (January 29, 1737 – June 8, 1809), Christopher Hitchens (April 13, 1949 – December 15, 2011) and President Jalal Talabani (November 12, 1933 – October 3, 2017).

Kani Xulam @AKINinfo

The original of this piece was published by NRT English, a Kurdish website out of Kurdistan, Iraq.

0 Comments