In 1985, a 23-year-old graduate of Columbia University was hopping from job to job in New York City trying to make a living. He came across a flyer that announced the upcoming lecture of a civil rights icon at his old alma mater.

The alumnus was Barack Obama. The icon Stokely Carmichael. He decided to go to the talk. “It was like a bad dream,” he reminisced about it, years later. He wasn’t sure if he should call Mr. Carmichael, also known as, Kwame Ture, “a mad man or a saint.”

Stokely Carmichael, after becoming an activist, hadn’t liked the names that had been given to him at birth in Trinidad in 1941. The island nation was a British colony. The Carmichaels were a loyal bunch. They had named their newborn, Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael.

In 1978, Mr. Carmichael discarded all his given names including his last name. He assumed the first name of Kwame Nkrumah, the liberator of Ghana and the shortened last name of Ahmed Sekou Toure, the liberator of Guinea. He called himself African, Kwame Ture, and lived in Guinea for the rest of his life.

Mr. Ture was in the news last summer. President Clinton paid him an underhanded compliment in the course of a eulogy for another civil rights icon, John Lewis. He got his share of criticism for doing so, but Mr. Lewis—had he been alive, if I have read him correctly, would not have joined the critics.

If the young Obama didn’t know what to make of Mr. Ture, the aging Clinton did and stated that although Mr. Carmichael had succeeded Mr. Lewis as the leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), his views hadn’t—and America was better off for it.

It was a reference to the clash of ideas that took place among the civil rights activists of 1960s. John Lewis and his friends remained true to their vows of nonviolence whose luminous patrons included the likes of Jesus Christ, Henry David Thoreau, Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

Stokely Carmichael, initially at least, was part and parcel of this fledgling movement as well. But his commitment to nonviolence was practical rather than moral. Before long, he gravitated towards the views of Malcolm X. Towards the end of his life, he even wore a pistol for self-defense.

Malcolm X and Dr. King were assassinated. Mr. Ture and Mr. Lewis died peacefully surrounded with their loved ones. Freedom was their goal. Freedom is also our aim. Can Kurds learn something from their examples? Who is a better fit for our needs?

In the rest of this essay I intend to focus on Mr. Ture and Mr. Lewis as civil rights activists. I plan to cite examples from their works to give you a sense of their personalities. I will then let you be the judge of who was a better agent of freedom.

This exercise in contrasting the lives of individuals has a history in antiquity. The Greek writer Plutarch famously compared the lives of renowned Greeks with those of celebrated Romans. He wanted, he told his contemporaries, “to arouse the spirit of emulation” in his readers.

That is to a certain extent my intention as well. Who knows—maybe, one day, a Kurd will walk in their footsteps? If she or he expands the boundaries of liberty in Kurdistan and the Middle East, I will credit my modest efforts worthy of freedom’s calling.

Stokely Carmichael wasn’t supposed to be a civil rights activist or a prominent organizer on both sides of the Atlantic. No one would have guessed his permanent emigration from America to Africa in 1968 or later. He attended the Bronx High School of Science. He was expected to be a healer of broken lives, an American doctor.

In fact, his father thought they would, upon his graduation, move back to the old country, open a clinic, serve the medical needs of the islanders and live there happily ever after.

The dawning of the 1960s changed all this.

History is replete with these kinds of seismic events that upend everything. When America was born in 1776 and France had its famous revolution in 1789, poet William Wordsworth wrote:

“Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive

But to be young was very heaven.”

Then it was the amazing burst of freedom that established a republic in America and another in France. In the 1960s it was the elegantly executed nonviolent struggle of blacks for equality that made America a better place for all.

The goal of equality though noble in aspiration has remained, alas, so far, beyond the reach of humanity. Karl Marx may not like it, but Aristotle, not without reason, had warned, “The worst form of inequality is to try to make unequal things equal.”

Mercifully, America was ready for the challenge. Only nonviolence had a chance of levelling the playing field in the United States. Two black Americans knew this and were ready for the task. The older one was Bayard Ruskin. The younger Reverend James Lawson.

The first persuaded Dr. King to employ Gandhian tactics during the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott. The second trained the likes of John Lewis to be the disciples of the Indian revolutionary with an American touch—working through church leaders and their flocks.

Mr. Carmichael was, at this time, still in high school.

His introduction to the civil rights struggle came with the first sit-in of the 1960s, the Greensboro Four, in North Carolina. Initially, he couldn’t be bothered. The students were after a publicity stunt, he thought. But when they persisted, his curiosity was piqued.

As luck would have it, a few weeks later, he was in Washington, DC for another protest. There, he noticed a group of well-dressed blacks, picketing just like himself, but possessing a level of kindness and firmness that he had never seen before.

He wanted to know all about them.

They were students at Howard University. They were members of a campus organization, Nonviolent Action Group (NAG). NAG was part of another organization, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). They all wanted to eradicate segregation in America.

Mr. Carmichael was hooked!

A few months later, he registered at Howard University as a freshman and joined the ranks of NAG with the enthusiasm of a new convert. Though new to Gandhian tactics, he soon came to know them and adopted them as well as he could.

Howard University is in the nation’s capital. Seventy-five miles east of it, segregation was practiced on the eastern shore of Maryland. The whites there were pursuing their American dream. The blacks were subjected to the withering effects of racism and exploitation.

NAG decided to be part of an effort to integrate the eastern shore. It joined forces with Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC), a sister organization. A segregated business was identified for picketing. Its owner was given advance notice—as Gandhi had instructed.

On the appointed day, Stokely Carmichael and his friends wore their Sunday best and drove to the designated site as if they were attending an important function in the United States Congress. Just like he had seen on television, they were subjected to a barrage of insults and assaults.

The NAG and CNAC people didn’t respond to the insults or get even with the assaults. They also didn’t give up. They continued with their orderly, peaceful, courteous and often festive protests day in and day out.

One day, a white man, Eddie Dickerson, knocked Mr. Carmichael to the ground and kicked him repeatedly in the stomach. In the evening, the protestors retired to a local church to lick their wounds and rest their bodies.

As Gandhi had thought it might happen, Mr. Dickerson, feeling the pangs of conscience, showed up unannounced. Several hours later, he left the place of worship transformed.

A few months later, he joined the movement and went to Georgia to atone for the sins of his race. He was beaten in turn and sent to the jail as well.

How did Mr. Carmichael react to the transformation of Mr. Dickerson?

There is only one passing reference to the incident in his voluminous autobiography. Nonviolence remained an enigma to him. He was in it for the sake of his friends. All he wanted was for blacks to have the same rights as whites.

He proved to be a resilient activist though. He spent his 19th birthday at the famed Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi for taking part in the Freedom Rides. William Faulkner, the famed American author, had immortalized the place as, “Destination Doom.” In 1961, it still held on to its grim reputation.

One day, when a guard was roughing up Mr. Carmichael, he burst out singing the old spiritual, “I’m gonna tell God how you treat me!” His friends joined him in chorus. They hoped for better treatment from their guards.

Alas, no noticeable change was noted in their manners.

Mr. Carmichael’s arrests were piling up, but he never neglected his studies. As he had promised his mother, he graduated on time and with distinction. Offered a scholarship at Harvard University, he opted for the life of a full-time activist in the South.

The year 1965 proved to be a decisive year for Stokely Carmichael.

The death of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a church deacon, acted as a catalyst. Mr. Jackson had been murdered while trying to protect his mother from the police beating. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) decided to protest the killing by marching from Selma to Montgomery.

A Sabbath, March 6, was chosen for the date. It turned into what is known as “Bloody Sunday.” Six hundred calmly marching blacks were attacked and gassed by state troopers under the command of Sheriff Jim Clark. John Lewis, leading the march, was beaten unconscious.

Dr. King then urged the people of faith across the country to come to Selma for a second march. Hundreds of Christian and Jewish leaders responded. It was scheduled for March 9. Governor George Wallace issued an order cancelling it and blocked it.

12 days later, by a court order, the third march was allowed to proceed.

Thousands took part in it including Dr. King and Mr. Carmichael. They marched along U.S. 80 and crossed the Lowndes County. For the local well-wishers the march for civil rights was as much of a draw as their beloved preacher, Dr. King.

If Dr. King saw thousands of adoring fans, Mr. Carmichael saw as many potential voters. He collected their names and addresses. He promised to visit them after the march.

He kept his promise and visited them with three other SNCC volunteers. Some surprising statistics were awaiting them. The county was 80 percent black. None of its 5,122 blacks had ever voted before.

SNCC volunteers visited these potential voters one by one. They taught its residents how to read and write. They educated their adult students about the workings of democracy and registered them to vote in the local and federal elections.

The progress was slow. It also felt dangerous at times. Mr. Carmichael was especially worried about their white volunteers who were sticking out like a sore thumb. Jonathan Daniels was one of them. He was a seminarian from Keene, New Hampshire.

But nothing would dissuade the whites from abandoning their posts.

Mr. Carmichael’s nightmare scenario happened on August 20. The blacks of Lowndes County and their SNCC volunteers had picketed a grocery store at Fort Deposit, Alabama on August 14. All were arrested. They were hauled to the detention center in a garbage truck.

The Keene native was one of them. Lacking bail money, they were all jailed. 6 days later, they were released. As they were waiting for their ride to arrive, Ruby Salas, one of the freed young girls, wanted to buy a cold drink. Mr. Daniels accompanied her to the nearby shop, Varner’s Cash Store.

Waiting for them was Tom Coleman, an unpaid special deputy, with a shotgun. He threatened them and pointed his gun at Ms. Salas. Mr. Daniels, fearing the worst, placed himself between the gun and the black girl. He was shot. He died on the spot.

Ms. Salas was unharmed.

When Mr. Carmichael heard the news, he had a nervous breakdown. He had known that he might be killed, but he was clueless as to how he would react to the death of a friend. He was too distraught to meet Jonathan’s parents, the Daniels. His mother accompanied him to Keene, New Hampshire.

After the funeral, Mr. Carmichael came back to Lowndes County to finish up the work.

Although he and his friends registered hundreds of blacks for voting, they ran into another problem. The existing parties offered no programs to help the blacks. But the laws of Alabama allowed for the formation of a new party. They set out to establish one that served their needs.

They called it the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). For a symbol, they chose a snarling black panther. Its platform read, “One Man One Vote!” “Black power for black people,” became one of its most popular slogans.

Competing with it were the establishment parties—the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. The latter was negligible in the South. The first had a white rooster as its symbol. Its platform read, “White Supremacy for the Right.”

In the midterm elections of 1966, the black residents of Lowndes County voted for the snarling cat. The words “Black Panther” soon supplanted the party’s initials, LCFO, in the news bylines. Although the cat lost to the rooster, there would be other elections.

The year that saw the “Black Panther” party compete with the “White Rooster” party for the elected seats of Lowndes County also saw the election of Stokely Carmichael as chairman of SNCC. But 1966 was also the year that he lost faith in nonviolence.

It happened in Mississippi, on June 17, 1966.

He had joined the march from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi after the shooting of James Meredith. The marchers had the permit to rest for the night of June 16 on the grounds of Stone Street Elementary School in Greenwood, Mississippi. Instead, they were gassed and arrested.

That night, in custody, Mr. Carmichael reached the end of his nonviolent rope.

Bailed out the next day, he vowed never to volunteer for arrests again and urged the crowd to repeat after him, “Black Power!” They did. Like the words, “Black Panther,” they have come to be known as his touchstones ever since.

A month later, Mr. Carmichael was in Chicago with Dr. King. Each was following his own schedule. The Chicago Daily News covered both events. They noticed that the young were gravitating to Mr. Carmichael; the adults to Dr. King.

Not just nonviolence was buried in Greenwood, Mississippi, but a different kind of politics took to the center stage with Mr. Carmichael. He once famously noted, “I am six foot one, 180 pounds, all black and I love me.”

“I love me” didn’t have much in common with humility, a cornerstone of nonviolence. Pride replaced modesty in the diction of Mr. Carmichael.

Freed from the constraints of nonviolence, Mr. Carmichael visited Europe and Africa including North Vietnam. Expressing solidarity with Ho Chi Minh, he denounced America’s military adventure in Asia. He adopted and popularized the often-quoted phrase of antiwar activists, “Hell No, We Won’t Go!”

He advocated a land mass for revolution and chose Africa as his base.

He thought the white people needed to return to Europe, the black people to Africa, but not the Jewish people to Israel. His new principles could, alas, accommodate exceptions. For him, Palestine belonged to Palestinians.

He spoke highly of Muammar Gaddafi of Libya. Unfortunately, he didn’t live long enough to see what the Libyans thought of his favorite African leader. Ahmed Sekou Toure, his patron in Guinea, became a dictator. Mr. Ture could, unfortunately, find no fault in him.

The same, you could say, happened to Abdullah Ocalan who could not bring himself to criticizing Hafez al-Assad, the Syrian dictator.

Mr. Carmichael held on to the hope of a worldwide revolution against the whites and their collaborators and always answered his phone with his signature answer, “Ready for revolution!” He wrote his autobiography on his deathbed and titled it with the same phrase.

Mr. Carmichael died of prostate cancer at the age of 57 thinking that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had cut his life short.

The man who lived a longer life was his friend, John Lewis. He died last summer at the age of 80. Three presidents spoke at his memorial service. The fourth, Jimmy Carter, sent a written message.

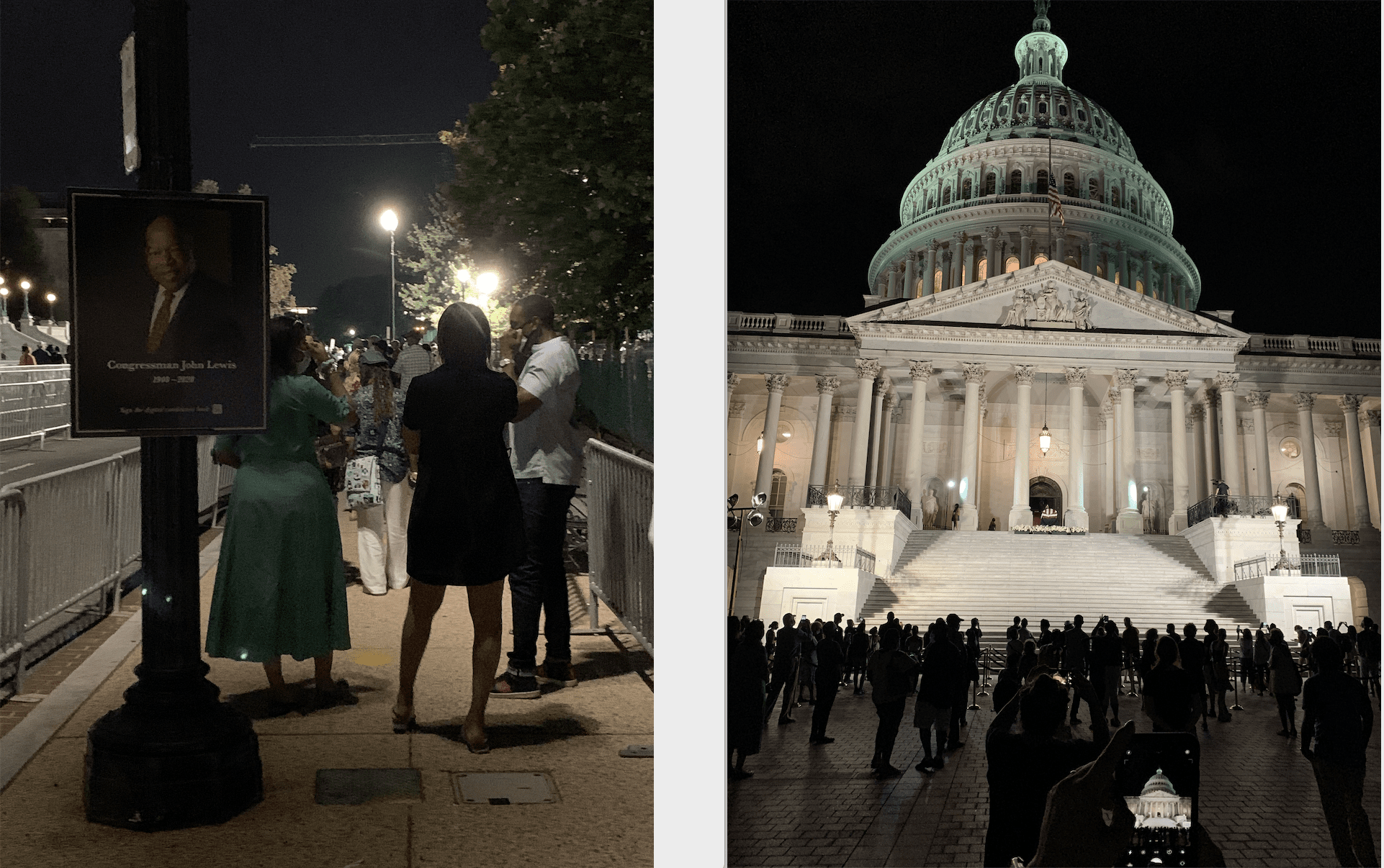

He became the first black to lie in state at the US Capitol Rotunda. I paid him my respects there along with thousands of other Washingtonians. I promised myself to introduce him to the Kurdish world.

Mr. Lewis too was not supposed to be famous, or a friend of presidents, or a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, or be awarded honorary degrees by Yale and Harvard.

When Mr. Lewis was 16 years old, he wanted to have a library card from the Pike County Public Library in Troy, Alabama. He applied for one but was told, only whites were issued library cards.

Forty-two years later, he was the author of a best-selling autobiography, Walking with the Wind. This time, he was invited back to the same library for a book reading and presented with a belated library card.

Mr. Lewis was born to a family of sharecroppers. For a long time, he was oblivious to the existence of whites. They just weren’t around where he lived. Perhaps that was a good thing. For when he finally met racism, he was able to keep it at a distance and fought it all his life.

He was in that sense like our beloved Musa Anter.

A loving family was his foundation. A loving God enlarged his heart to concern himself with his American family, black and white alike, and then the whole world and its myriad problems.

In 1955, Mr. Lewis heard Dr. King on the radio. Through the newspapers, he followed the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He felt personally vindicated by its success. Young John had always wanted to be a preacher. Now he had a role model.

But he was poor.

As his luck would have it, his mother worked at an orphanage and would come home with old newspapers and magazines. One day, she brought John a brochure about a school that trained preachers for black folks with an aid package as well.

It was in Nashville though. It was called American Baptist Theological Seminary. Young John didn’t want to work in the fields. The family was worried about sending him to another state.

He persisted. He prevailed. He applied. He was accepted.

In 1957, Mr. Lewis left home to become a pastor. In the fall of 1959, he was invited to a series of evening workshops on nonviolence at Clark Memorial Methodist Church in Nashville.

Reverend James Lawson, a disciple of Gandhi, was teaching them. A dozen or so students of the area universities had signed up. Mr. Lewis did too. John bonded with these students and they all bonded with their teacher.

Years later he would write of his introduction to nonviolence, “It was something I’d been searching for my whole life.”

They learned of something called redemptive suffering: That anguish could be liberating. That it could also cleanse the soul. That it affected not just the sufferer, but everyone—those who inflicted the suffering and those who witnessed it too.

Redemptive suffering had a way of stirring the conscience of an individual or individuals. It touched hearts and forced people of goodwill to feel compassion and those of ill will guilt.

Between 1960 and 1966, John Lewis was arrested forty times. He was repeatedly beaten by white supremacists, state troopers, shopkeepers and sometimes shoppers.

In Selma, his skull was cracked; in Montgomery, he was left for dead in a pool of his own blood. Often captured on film, the attacks on unarmed and well-dressed disciples of Gandhi weren’t just national news, but international news as well.

The black America was insisting on change and the white America was struggling to accommodate it, but sometimes it took decades for the tree of nonviolence to bear fruit.

In 1961, John Lewis joined 6 whites and 6 blacks for the first of many Freedom Rides to challenge the segregation laws of the South. They boarded their buses in Washington, DC and hoped to reach New Orleans, Louisiana 13 days later.

In Rock Hill, South Carolina, a white mob was waiting from them. Mr. Lewis was attacked for wanting to use “Whites Only” waiting room.

He was beaten and bloodied. When the police showed up, he was asked if he wanted to press charges against his assailants. He didn’t. What he wanted was for the police to help him enforce the laws of the United States that banned separate facilities in the United States.

Forty-eight years later, a white man requested a meeting with John Lewis. His name was Elwin Wilson. He said he was from Rock Hill, South Carolina. He had come to ask for forgiveness.

Mr. Wilson like Mr. Dickerson was duly forgiven.

Some hearts were beyond redemption though. One of them belonged to Sheriff Jim Clark of Dallas County, Alabama. He had ordered his troopers to gas and attack 600 peaceful marchers that had wanted to walk from Selma to Montgomery on March 6, 1965.

A year later, with the help of newly registered black voters, Sheriff Jim Clark was soundly defeated in the election. Instead of respecting the will of the people, he brooded and wrote a memoir calling it, The Jim Clark Story: I saw Selma Raped.

It didn’t sell well. He ended up selling mobile homes to keep a roof over his head.

In the summer of 1964, an American journalist from New York volunteered to be a teacher in Greenwood, Mississippi. A black family hosted her. She thought she was going to teach them literacy to hasten their emancipation.

She witnessed something else.

She wrote, “They [the blacks] disarmed the enemy [the whites] with their gift of sight beyond surfaces. But ‘the enemy’ was not a category; their love was color-blind and reserved for what was important.”

For example, “Mrs. [Fannie Lou] Hamer was free. She represented a challenge that few could understand: how it was possible to arrive at a place past suffering, to a concern for her torturers as deep as that for her friends.”

She concluded, “Such people are rare. All of them began by refusing to hate or despise themselves.”

“A place past suffering,” in the words of Sally Belfrage, redeemed America. Coupled with the nonviolent protests that involved thousands, they forced those who speak for America to do some serious soul-searching:

It just didn’t add up that America was supposedly fighting for liberty in South Vietnam while tolerating the domination of one race over the other at home.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law first the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and then the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Given the scope of this revolutionary change, it was a miracle that only buckets, not rivers, of blood were shed in the South.

The “place past suffering,” I believe, is capable of redeeming Kurdistan too, removing the hatred the Kurds feel for their oppressors from their hearts replacing it with a feeling of concern for their tormentors as well as their compatriots.

Think about it: suffering can be turned into wisdom and love!

Reverend James Lawson played a big role in all of this. John Lewis rightly credited him with his accomplishments, “I couldn’t have found a better teacher than Jim Lawson. I truly felt—and I still feel today—that he was God-sent.”

Not since Plato honored Socrates has the world seen another example of as well-earned a praise as that of Mr. Lewis for his beloved teacher, Mr. Lawson.

Reverend James Lawson hasn’t been the only one receiving accolades.

23 years after meeting Mr. Ture at Columbia University, Barack Obama became the first black president of the United States. After his inauguration, John Lewis, then a Congressman, approached him for an autograph for his inauguration invitation.

The 44th president of the United States complied. He wrote, “Because of you, John,” on the invitation program and then autographed it.

It was the heartfelt homage of a young president for an aging activist. It will be remembered for as long as there is the United States of America on this earth.

The original of this essay first appeared on the website of Kurd Arastirmalari

Kani Xulam on Twitter @AKINinfo

0 Comments